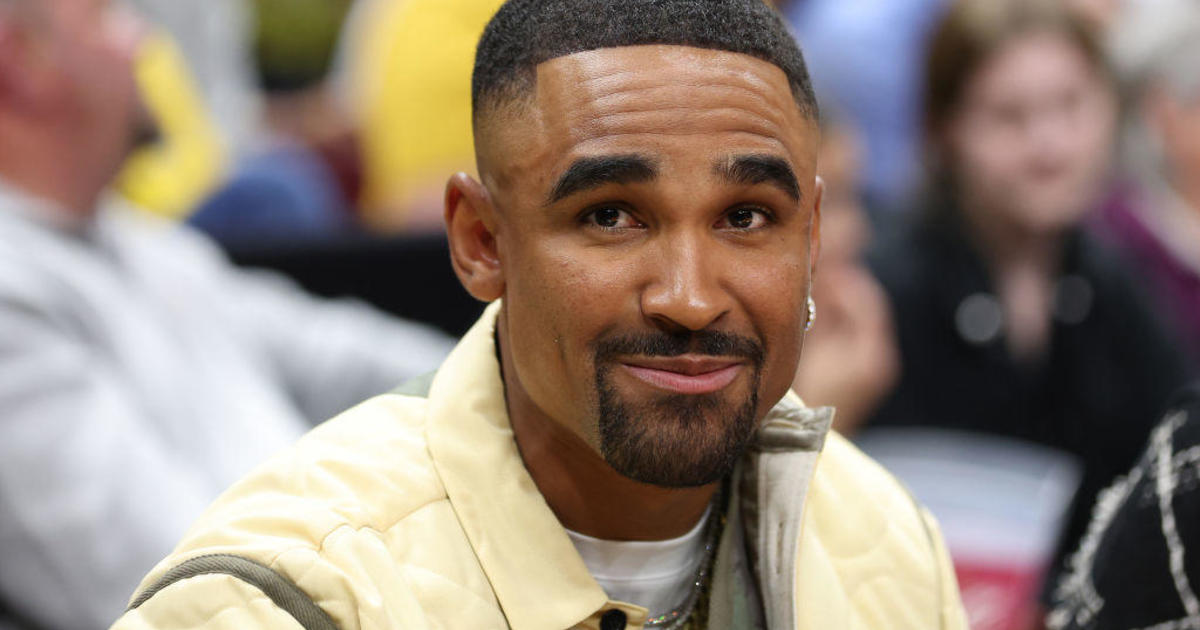

Meet Paralympic Wounded Warrior Brad Snyder

By Joseph Santoliquito

Baltimore, MD (CBS)—Brad Snyder can still see in his dreams. He can envision himself churning through the water. He can see himself standing on a podium. And receiving a gold medal. Then he opens his eyes and sees black.

On September 7, 2011, Snyder went from an Afghanistan village to a world of darkness 60 hours later listening to the comforting voices of his parents. He went from someone who never cowered in the mouth of danger to someone reaching out with each step.

Picture the William James character from the movie "The Hurt Locker" walking down a barren street to defuse a bomb and you have a good idea what kind of a job the 28-year-old Navy lieutenant held in Afghanistan. He lost his sight when an improvised explosive device (IED) exploded nearby—and that forced him to return to a passion that's evolved into more than what he expected.

Snyder, still on active duty, will be competing in seven swimming events as a representative of the United States Paralympic team. He was a competitive high school swimmer who went on to swim for the Naval Academy.

He can still see in his dreams.

That's something September 7, 2011 couldn't take away.

"I'm fortunate to have all these capabilities and what I do honors them," Snyder said. "On September 7, 2011, I was on a patrol that was half-Afghan and half-U.S. shortly after sunrise. We landed from a helicopter and taken a strongpoint in a village. After we switched our gear, we decided to move to another village where we were on foot patrol. I was halfway in the middle of the patrol, and my teammate was in front.

"That's when I heard a blast plume go up, and I knew it was an IED because of the size of the detonation. The size was consistent with the IEDs we had been seeing. I thought it hit my teammate, a U.S. man, up front—so we waited for a moment for some news over the radio. We assumed the worst—but two Afghans were badly injured."

Snyder's unit was able to safely evacuate the first Afghan. But the second Afghan needed a litter to be moved. Snyder and a group of soldiers went off to get a litter, and upon their return, an IED exploded four feet in front of Snyder.

He remembers hitting the ground with a thud—although everything was okay. He checked. Everything was where it should be. Snyder's unit told him he looked fine—from the neck down. But his face was in incredible pain.

Snyder was medivacced out, underwent a medically induced coma and incubated for 60 hours. He woke up in Walter Reed Hospital, where his family was there to meet him. What followed was a rigorous six-day process that involved a series of surgeries in an attempt to regain his vision.

"It was an interesting conversation we had with doctors," Snyder recalled. "I had a suspended view of reality. You go from the mindset of being on patrol in Afghanistan to waking up with your parents here in the States. It was a sobering conversation with the doctor. I remember asking what my chances of seeing again were and doctor telling me I had a one-to-two-percent chance of seeing light out of my right eye. I remember hanging my head for a moment, but my family was there and I had to be strong for them—because they were strong for me."

Then Snyder went in a fast-forward mode. He would have to begin figuring out new ways to eat spaghetti.

"I would have been silly to do the job I was doing and think I wouldn't get injured," Snyder said. "I had a lot of friends who paid the ultimate sacrifice, and I had no one to blame but myself for what happened. I had a choice to make, move forward. Instead of blaming myself, I decided to move on.

"I learned an immense amount about myself. What happened reaffirmed the character aspects my father taught me as a child, and what I learned at the Naval Academy. Go to Memorial Hall at Navy, and there's a large flag that says, 'Don't give up the ship.' That kind of mentality is imbued in you through difficult things. It's what you learn at Navy, and it's what my father was big into—not giving up."

Gumption and stubbornness have been his two-word mantra. He would have his difficult days, when routine, like the amount of tooth paste on a tooth-brush or when water is boiling, became frustrating. Swimming never was. Snyder had been a competitive swimmer for 11 years.

He began swimming again. It's where he felt most comfortable. It's what made him feel refreshed and instilled renewed vigor. He got in touch with Rich Cardillo, who started the United States Association of Blind Athletes in January 2008.

Snyder needed permission to leave Walter Reed for an hour a day, three days a week to swim. He was introduced to Paralympic swimming. He was rehabbing while still on active duty. He opted to compete—swimming in the Jimi Flowers Meet in April and did reasonably well.

That triggered it. Snyder went after a Paralympic place. He's been working with Brian Loeffler, Loyola's swimming coach. He may need to be tapped in the head by a roped foamy noodle to know when to stop, and he may not be ripping through the water as he when he swam for Navy.

Yet Snyder has qualified for seven Paralympic events, and his times for F-11 (totally blind category) swimmers in the 100-yard freestyle (57.7 seconds) and 400 freestyle (4:35) are the fastest in the world.

"I use jokes as a mechanism to make people more comfortable around me, because being blind doesn't bother me at all," Snyder said. "I can joke—and if you can't laugh at yourself, who can you laugh at, right? I want to be autonomous. I don't want handouts or help.

"Autonomy is what I most want. I don't like needing help. That's been the hardest thing to get past—because I was a go-getter and I was after high-speed things. Maybe I need someone to lead me to the elevator at times, and that can be humbling."

Snyder will arrive in London, England, where the Paralympic Games will take place, on August 27th. "For a while, it was surreal," Snyder said. "When I dream, I can still see in my dreams. Then I wake up, I remember that I can't see and find my way to the bathroom. But I can get up on my own. I have reached a nice comfort zone. I have a true awareness of what I'm able to accomplish."