Emotion High Over New Jersey Plan To Close Disability Home

VINELAND, N.J. (AP) -- Karen Lee Colletti has severe autism, speaks only a few words and needs a diaper. When she was 27 and her parents felt they couldn't care for her at home any longer, they moved her to the Vineland Developmental Center, which cares for women with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

That was 29 years ago. Now, her 80-year-old father, Vito Colletti, fears the state's plans to close the center by 2013 will happen, pushing his daughter out of a place that he thought she could live for the rest of her life. It's discomforting for a man who's come to rely on the care she gets at the state institution. After a hard time difficult adjustment from a move last month from one part of Vineland's campus to another, he fears a longer move to one of the state's remaining institutions would "drive her bananas."

He's joined the fight of the 1,300 developmental center employees who could lose their jobs—and officials around the southern New Jersey community of Vineland—in trying to persuade the state to leave the center open.

The effort to save the center has brought rallies and efforts by some lawmakers to remove money from the proposed state budget that would pay for costs associated with its shutdown.

Among those in favor of closing the Vineland facility are advocates for people with disabilities like autism, cerebral palsy and seizure disorders, who say that only by closing developmental institutions can the state afford to place more people with disabilities into less restrictive settings like group homes.

They point to former Vineland residents like Estelle McGurk, 48, who moved earlier this year into a group home, where she's learned some cooking skills, gone to a play and made new friends. McGurk was apprehensive about leaving Vineland at first, but she's taken to her freer life. "It's better here," she said.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1999 that it's unconstitutional segregation to keep in institutions people who want to move out, who are determined by guardians and caregivers as able to do so. New Jersey has lagged behind most states at moving people out of institutions.

"Our position is that the priority must be given to the people in these institutions who want to leave," said Joe Young, executive director of Disability Rights New Jersey, which is suing the state to try to force closure of some developmental centers. "The problem is, their interests are always coming last."

Vineland Developmental Center has two campuses on 250 acres of flat land in southern New Jersey—a total of 49 buildings, some of them imposing 19th century structures with columns. It opened in 1888 for the care and teaching of girls and women with developmental disabilities. Back then, it was unusual for a state government to provide care and education for people with disabilities.

"Initially, we did things better than everybody else," Young said. "Then we got stuck."

To advocates like Young, the developmental center approach— creating self-contained communities, often in rural areas, staffed with specialists—is outdated because it's based on the notion that the developmentally disabled should be secluded, unable to be a part of general society.

In recent decades, it's become far less common for girls or young women to be sent there by their families. And growing numbers of them, with the support of their guardians, have moved into less restrictive homes. In 1984, the state had more than 5,700 people at its 11 developmental centers. By the end of 2010, the number had dipped to fewer than 5,700 at seven centers. Four centers were closed in the

1990s.

Still, nearly one-fifth of the developmentally disabled people for whom New Jersey pays for housing remained in state-run institutions.

That's a rate nearly three times the national average and higher than any state except Mississippi.

Vineland, which still serves only women, saw its population drop from about a high of more than 2,000 in the late 1950s to fewer than 400 by December, largely through attrition. Young says that by keeping it open, the state has less money to move developmentally disabled people into less restrictive environments that would be better for them.

Gov. Chris Christie, who supports closing Vineland, says that on this issue, his main concern is doing what's best for the residents, not saving taxpayer money, though that is expected to be a benefit of closing the center.

The state says it costs an average of $260,000 per year in state and federal money for someone to live in a developmental center. That includes health care costs.

It costs, on average, $160,000 per year for someone who previously lived in a center to be in community-based housing, most often a group home. That figure does not include Medicaid-provided health care and administrative costs. Human Services spokeswoman Pan Ronan says those costs average nearly $8,400 for Medicaid and $3,400 for administrative costs.

Closing the campus, which is among the biggest employers in Cumberland County, could be a big loss for the area.

Assemblyman Matthew Milam, a Democrat from Vineland, said closing it would hurt not just the families of those who work at the center, but also vendors and others in an area with a fragile economy. And, he said, that breaking decades-long bonds would be hurtful. Two-thirds of the Vineland center residents have been there more than 30 years; nearly half the staff has been there at least 20.

"To have that separation," Milam said, "it would be devastating."

Vito Colletti, whose daughter is at Vineland, said that while moving to a community setting makes sense for some people with disabilities, his daughter is not a candidate to live somewhere less restrictive.

"That type of staff cannot handle her," said Colletti, who lives in Port Reading and makes the 200-mile roundtrip drive to see his daughter every other week. "She needs 24-hour care, hands-on."

Even the advocates who call for Vineland to be shut down say they believe the care there is generally good. Their objection is the intrinsic confinement of an institution.

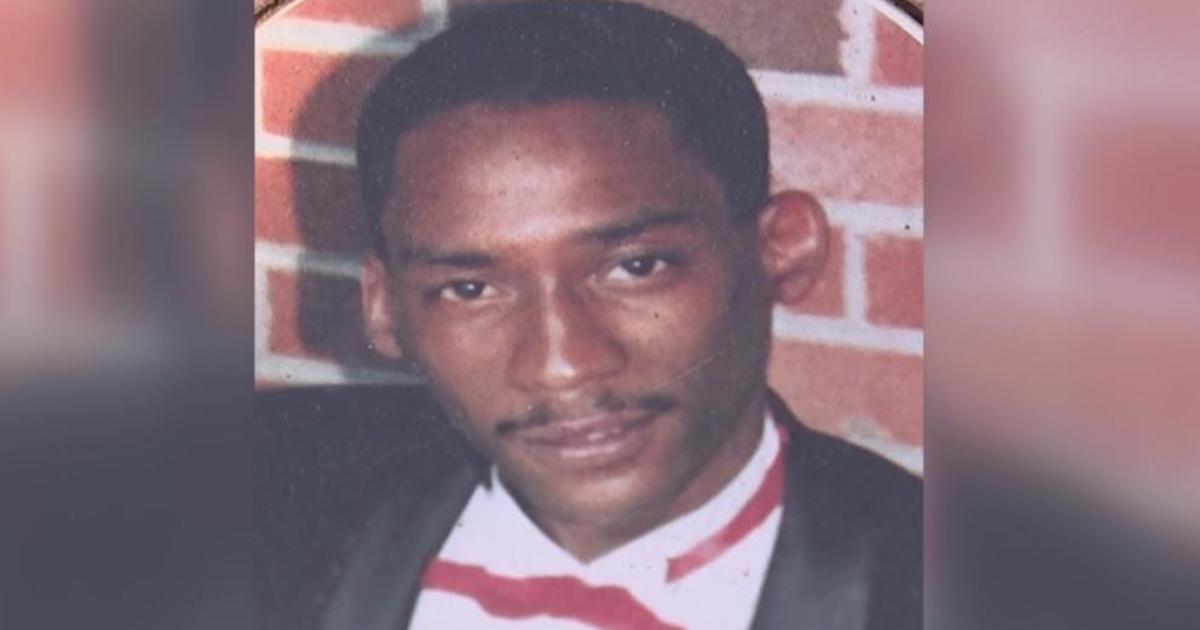

Willie Mae Powell-Roberts, now 64, began working at Vineland 40 years ago and loves her work so much that she often arrives an hour early.

She talks about building a bond so strong with one woman with behavioral problems that the woman's aggression subsided and organizing shopping trips for clients.

"We became family," she said. The residents, she added, "know your days off. They know what automobile you drive."

The state Human Services Department plans to shut down Vineland by 2013. Clients who want to could go to homes in the community— mostly small group homes run by providers with state contracts. Some are for-profit groups, some are nonprofit. Remaining residents would be moved to other institutions around the state.

Many could be moved to homes similar to the one where Estelle McGurk now lives.

McGurk, whose diagnoses include cerebral palsy and osteoarthritis, needs a wheelchair to get around. She lived much of her adult life at Vineland before she moved earlier this year to a new four-unit group home built by the nonprofit Arc of Atlantic County.

Currently, three women live in the home. Staffing in group homes varies by the needs of the residents, but like others where residents are not able to walk, hers has at least two staff members present whenever the clients are home. There are generally more staff per resident in group homes than in Vineland, which employs 1.5 caregivers per resident.

Advocates for moving people from institutions to community settings—many of whom are associated with groups that provide services to people with developmentally disabilities—say that almost everyone can live outside an institution with the right amount of help.

McGurk was happy in Vineland.

"I had all my friends," she said. "They knew how to bathe me.

They knew how to take care of me."

In her new home, she has a small kitchen, a private bathroom, a sitting room and a bedroom decorated in pink. She can listen to her beloved Gladys Knight music whenever she wants. She's been to see a high school's production of "Hairspray" and has been visited by two teachers from Vineland.

It's a different life than the more regimented one in Vineland, where she shared a large bedroom with five other women.

Like others who live in group homes in New Jersey, she takes a van to a nearby day program each weekday. And, she said, the caregivers at her new home are able to provide the care she needs.

Now, she's going out to church every Sunday morning. Before, she said, she also attended services—but only on the campus.

Part of the cost difference between types of facilities comes because the developmental centers have staffs to attend to needs from medical care to fixing leaks. Wages of workers are another factor.

The average direct-care worker at Vineland has been there almost 13 years and makes nearly $44,000.

Scott Hennis, operations director at the Arc of Atlantic County, a nonprofit organization that provides services to developmentally disabled people, said the starting salary for workers in his organization's homes is usually around $10 an hour.

Kim Todd, executive director of the New Jersey Association of Community Providers, a group whose members would expand their capacity if Vineland is shut down, said that while the workers have legitimate worries, they shouldn't be at the heart of the closure debate.

"There are consumers that have been waiting for decades to leave," she said. "Why is it we would support withholding a life from somebody based on a workforce issue?"

(Copyright 2011 by The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved.)